NoSQL, a transitory technology

I recently watched this talk on Advanced DynamoDB Design Patterns in preparation for some upcoming work. I ended up watching it multiple times and sharing it with colleagues because I felt it gave me, a relative outsider to the NoSQL world, a good feel for what it’s all about and why people have been using it.

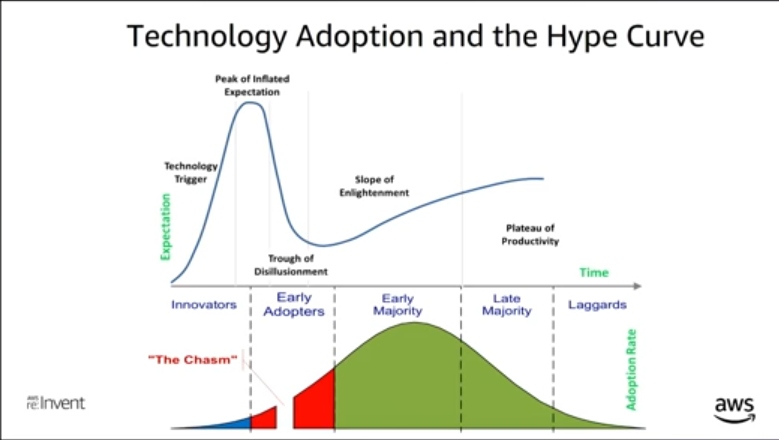

The presenter states that we have yet to hit the “slope of enlightenment” with regards to NoSQL adoption because most people who are currently using it are not using it properly.

The gist of it is that NoSQL is quite unforgiving and you need to be very clever up front in the way you model your data to fit all your access patterns. One of the recommendations made is to put all your data in the same table or key space. You then use clever combinations of composite keys in your partition and sort keys to differentiate the types of data and have efficient look-ups. This is reiterated in this AWS documentation about NoSQL design best practices.

It must be a lot of fun to be a NoSQL consultant. You go in to a company, work with them to enumerate all their access patterns and then design an extremely clever one-table contraption that performs well and is capable of holding practically infinite amounts of data. You then hold the new table design up in the air like a solved Rubik’s cube, everyone is happy and a big check clears in your bank account for a job well done. It would be interesting to see how that “solution” holds up 1 or 2 years down the line.

If proper NoSQL design must be done “up-front” and with complete knowledge of the access patterns, then it is by definition a type of database that is only suitable for mature systems/workloads that are unlikely to drastically change in the future.

There are lots of disadvantages to a lack of schema. Optimal read/write patterns must be documented somewhere and maintained. When you have a defined schema they are up-front and obvious. By looking at the column types and the indexes you can easily know the most optimal ways to access this table.

If I use one table and index overloading, then all my records must contain within themselves some metadata about their type. For example, for Orders I have to write the partition key as Order_<key> instead of just <key>. No big deal, disk is cheap in the cloud right? Yes. But IO is not. Every time you are reading that record you are reading an extra 8 bytes. DynamoDB offsets that somewhat by charging you in units of 1KB but different systems may charge you based on total IO. The extraneous metadata may also cause some records to spill over from 1 write unit to 2 write units.

Operationally, things become tricky too. Let’s say you discover a bug with your pricing engine and you need to update all your Orders to reflect the new correct price. How do you know you got all of them? How long would it take to check a 50TB table that all your orders are properly formed? How complex and error-prone would that script that performs the check need to be?

It turns out that the combination of schema and a declarative API are extremely powerful and the industry is starting to realize that. I guess the lesson here is when evaluating new approaches, be sure to consider fully what you are giving up.

NoSQL databases abstract away the scaling/partitioning by providing a simple interface over a cluster. This allows devs to remove complex sharding logic from the application layer. This abstraction was generally achieved by stripping away a lot of the functionality and guarantees of a SQL database. We are now seeing these same databases trying to play catch-up on functionality. DynamoDB transactions or Cassandra Query Language are some examples of those efforts. It will be tough sledding for them to catch up on the decades of development that have gone into Postgres, MySQL or SQL Server.

What if you could solve the scaling problem without losing all the functionality and guarantees of a SQL database? That is harder and evidently has taken more time than the approach that NoSQL databases took. There are currently many ongoing attempts to solve this problem, I would class them as cloud-native databases and sharding middleware.

A Cloud-native database is one where the storage engine is rewritten to suit the properties of the high-scale storage services the cloud companies have built. By plugging in this made-to-measure storage engine to battle-tested database engines, you end up with a product that is both rock-solid and highly scalable. Amazon’s Aurora is a great example of this approach. By leveraging MySQL’s composable storage layer architecture, they were able to provide a superior database product without rewriting the entire thing. With the core of it still being open-source means that it only costs a bit more than a “regular” MySQL hosted in the cloud. A great win for customers in my opinion. The other providers also have equivalent offerings such as Google Spanner and Microsoft/Azure Cosmos.

The sharding middleware components allow a traditional database cluster to be abstracted away. You write SELECT foo FROM bar WHERE tenantId = 'abc' and the query router runs that query on the node which contains that data. Examples of these are Citus (Postgres) and Vitess (MySQL).

To my knowledge there is not yet a cohesive well executed combination of these two approaches, but when it comes there would be very little reason to use NoSQL databases.